The late winter sky over the Klamath Basin is cold, and painfully blue, and empty. I’m standing at the edge of Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge on the California-Oregon border. It’s a spot where I’ve been coming for years to be awestruck by clamorous hordes of thousands of Snow and White-fronted Geese. This time of year, the refuge should be teeming. On my visit, however, not only are there no geese, but there is no lake, only an expanse of dry, cracked mud extending to the horizon.

In a normal year—ah, there is that word: normal. If the year chosen as normal was, say, 1905, then the sky would have been filled with uncountable millions of Snow, Ross’s, Canada, and Greater White-fronted Geese, Tundra Swans, Northern Pintails and Shovelers, American Wigeons, Gadwalls, Mallards, Canvasbacks, Redheads, Ring-necked and Ruddy Ducks. In that year, the pioneering Oregon ornithologist William Finley as “the greatest feeding and breeding ground for waterfowl on the Pacific coast.”

At Finley’s urging, President Theodore Roosevelt established the “Klamath Lake Reservation” in 1908. Today known as the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, this was the first federal refuge created to protect waterfowl. Over the next 20 years, three additional national wildlife refuges were established in the basin: Clear Lake, Tule Lake, and Upper Klamath. An estimated of the waterfowl traveling the Pacific Flyway rely on these Klamath Basin refuges as stopover sites in spring and fall migration. Later designation of the Klamath Marsh (1958) and Bear Valley (1978) National Wildlife Refuges completed today’s Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex.

If the “normal” year was half a century later, then the numbers of ducks and geese would have been impressive still, but no longer uncountable. In 1958, migrating waterfowl numbers in the Klamath Basin peaked at 5.8 million birds, as estimated through aerial surveys by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). Such abundance has never been seen again. Waterfowl numbers have never exceeded 1 million birds in the past 50 years, or half a million in the past 20 years. This year, the peak waterfowl estimate was around 93,000. This is the lowest peak ever recorded—a tiny fraction of the plenitude that the Klamath refuges were established to protect.

It’s not just the Klamath Basin that’s in trouble. The same story—relentless decline culminating in a shocking crash in winter waterfowl—is playing out across the refuges strung like pearls along the Pacific Flyway, places sacred to Indigenous groups, conservationists, waterfowl hunters, and birders: Oregon’s Malheur, Utah’s Bear River, Nevada’s Stillwater, California’s Sacramento. Everywhere, the fear is growing that this emptiness, this winter silence, is normal now.

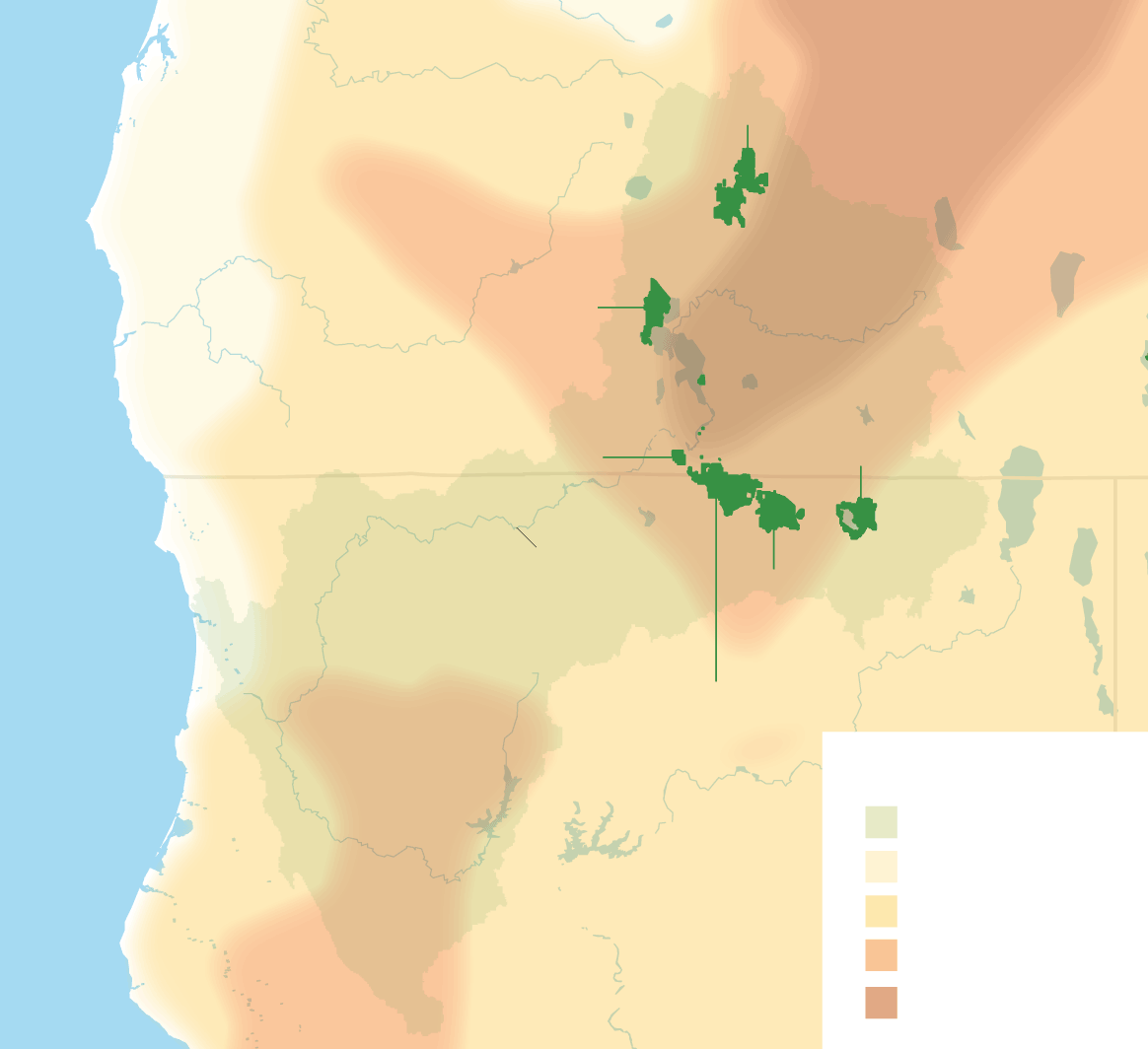

Klamath Marsh

National Wildlife Refuge

OREGON

Upper Klamath

National Wildlife

Refuge

Clear Lake National

Wildlife Refuge

Bear Valley National

Wildlife Refuge

Klamath River

Tule Lake

National Wildlife

Refuge

Lower Klamath

National Wildlife Refuge

KEY

CALIFORNIA

Klamath Basin

Moderate Drought

Severe Drought

Extreme Drought

Exceptional Drought

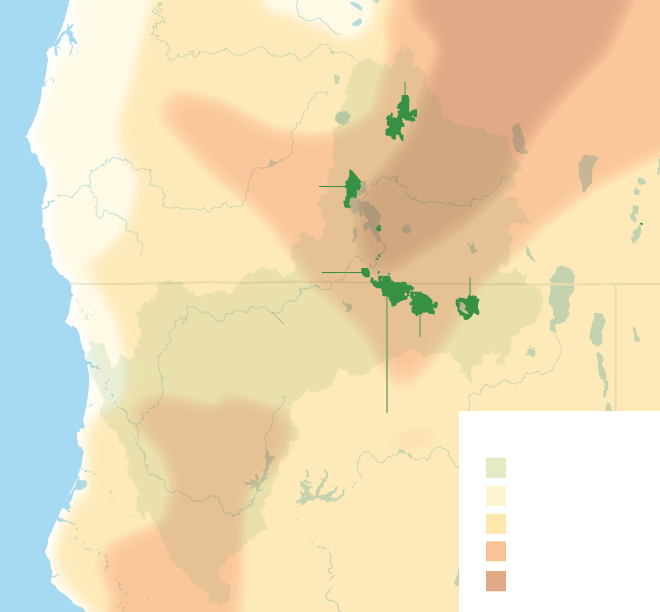

Klamath Marsh

National Wildlife Refuge

OREGON

Upper Klamath

National Wildlife

Refuge

Clear Lake National

Wildlife Refuge

Bear Valley National

Wildlife Refuge

Klamath River

Tule Lake

National Wildlife

Refuge

Lower Klamath

National Wildlife Refuge

KEY

CALIFORNIA

Klamath Basin

Moderate Drought

Severe Drought

Extreme Drought

Exceptional Drought

W

hat happened? It is a complicated history, in which human enterprise and human greed, expansive dreams and short-sighted actions, promises both well-meaning and cynical, disease and drought and suckers and salmon all play a part. But really, it all comes down to one word: water.

From time immemorial to the late 1800s, the vast wetlands of the Klamath Basin were a wildlife wonderland that can scarcely be imagined. Upper Klamath Lake—the largest in Oregon—was filled with c’waam and koptu, the sucker fish that formed a dietary staple of the native Klamath and Modoc peoples. Downstream, Lower Klamath Lake fully deserved its common description as “the Everglades of the West,” with floating islands of tule reeds that formed the platforms for great nesting colonies of American White Pelicans, Double-crested Cormorants, gulls, terns, and grebes.

After meandering through the basin’s landscape of marshes and lakes, the Klamath River flowed south across the California border and on to the Pacific, where swarming chinook and coho salmon entered to begin their journey of hundreds of miles to prime spawning habitat. These salmon were central to the diet and culture of Native peoples along the lower river, including the Karuk, Yurok, and Hupa. The river’s year-round flow was sustained by the slow melt of deep snowpack in the mountains forming the headwaters of the Klamath and its tributaries.

The first wave of destruction began in the 1890s, when commercial hunters descended on the basin. Some were hunting waterfowl to satisfy the demand for meat in San Francisco; others were plume hunters targeting egrets and the warm, lustrous feathers of grebes. The scale of the slaughter was staggering, but given time and protection—and preservation of their habitat—the populations of these birds might have eventually returned to their former abundance.

But a more irrevocable change came to the Klamath Basin in 1905, when Oregon and California ceded the lands under Lower Klamath and Tule Lakes to the federal government. The U.S. Secretary of the Interior promptly directed the U.S. Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation) to reclaim the lands beneath both lakes for the primary purpose of homesteading. To reclaim the land meant to drain the lakes and marshes, exposing the lakebeds for grazing and farming.

Despite Roosevelt’s 1908 declaration that the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge was to be protected “as a preserve and breeding-ground for native birds,” the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) initiated the construction of levees to control the flow of water throughout the basin. The draining of Tule Lake began in 1912, and of Lower Klamath Lake in 1917. During this same period, utility companies built a series of major dams on the Klamath River downstream from the basin, cutting salmon off from hundreds of miles of spawning habitat. The whole vast Klamath watershed became an engineered system.

Today there is no lake at Lower Klamath Lake, and recent spatial imaging analysis by refuge staff indicates that close to 95 percent of the basin’s wetlands have been lost, most converted to pastureland and irrigated agriculture. There is currently so little water that, of the 90,000 acres of protected “wetland” habitat in the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake refuges, a grand total of 3,500 acres at Tule Lake remain viable for waterfowl. At Lower Klamath there are no wetlands whatsoever. The Everglades of the West looks like something out of the Dust Bowl.

This is partly the result of the megadrought gripping the West, which scientists believe is . But it is also a problem of water policy. In the complicated and contentious assignment of “water rights”—legal access to a specified yearly amount of water—the Klamath Basin wildlife refuges are guaranteed precisely nothing. Instead, they receive whatever is left after other users get their promised allocation. And in most recent years, there are no leftovers at all.

There have been years of litigation over the basin’s water, between BOR, the Klamath Water Users Association (representing farmers), the tribes in the Upper Klamath trying to preserve the sucker fish, the tribes along the Klamath River trying to preserve salmon, and various environmental groups trying to assure a water supply for the refuges. Conflicts have steadily increased as it has become abundantly clear that more water has been promised than the basin can deliver.

Those tensions drew national headlines in 2001 when the BOR, amid a punishing drought, shut off water to irrigators to save fish downstream. The shutoffs sparked weeks of tense confrontations between farmers and federal authorities. Some of the intervening years have been a bit wetter, but the trend has been relentlessly downward, and the crisis has only deepened.

In the summer of 2020, another drought led to a catastrophic outbreak of avian botulism at Lower Klamath and Tule Lake. Waterfowl were crowded together in shrinking pools of warm water, ideal conditions for the botulism bacteria, Clostridium botulinum. There are several strains of this bacteria, and birds are highly susceptible to the toxin produced by Strain C (which does not affect humans).

Death by avian botulism is gruesome. Infected birds lose their ability to walk, then to control their wings. Unable to hold up their heads, ducks often drown in the water that should give them life.

Thanks to the heroic efforts of refuge staff, the rehabilitation organizations Bird Ally X and Focus Wildlife, and volunteers from the California Waterfowl Association (CWA) and other groups, as many as 2,500 affected birds were successfully treated and released. Tragically, however, as many as 60,000 died, from delicate little Green-winged Teal to Northern Shovelers to elegant American Avocets—35 species in all.

The following winter was even drier than the one before, and I had great fear that last summer would bring another outbreak of botulism. Thankfully, it didn’t happen. The reason, however, was hardly cause for celebration: The drought was so extreme that the refuges received no water at all. As a result, there were too few waterfowl to support a major botulism outbreak.

Looming over everything is ĂŰčÖAPP change. A recent study documented in wetland surface area across major watersheds in the intermountain West from 1984 to 2018. The study concludes that “a regional tipping-point in ecosystem water balance has been reached,” with demand consistently exceeding supply.

As of March 1, the shows almost every refuge on the Pacific Flyway at either severe (California’s Central Valley), extreme (the Great Salt Lake region), or, worst of all, exceptional drought (most of the Klamath Basin and Malheur). Even if the drought eases, ĂŰčÖAPP models predict that less and less of the region’s precipitation will fall as snow. This will have huge effects, as the slow release of melting mountain snowpack is crucial for nourishing wetlands and refilling aquifers.

T

his mounting water crisis places the FWS in an untenable position: The Endangered Species Act (and associated litigation) requires the agency to prioritize the needs of endangered salmon and suckers above all else, which means allocating the scarce available water to Upper Klamath Lake and the Klamath River. Meanwhile, the FWS is also responsible for preserving the wetlands and waterfowl that the basin’s refuges were established to protect. Again and again, the needs of these neglected refuges have lost out. The frustration of refuge managers and biologists is palpable. In a recent public briefing, they stated that “proper waterfowl and wetland management is impossible” under current conditions. “Waterbird populations are not only the lowest in the refuge’s history but importantly [are] Klamath Basin-wide, indicating a collapse of the most important staging area in the Pacific Flyway.”

Meanwhile, the BOR implements its water deliveries to fulfill federal water contracts with irrigators. Unless compelled by litigation, it does this without regard to wildlife, or fish, or habitat. Just this year, the BOR refused to release a small discretionary allocation to the refuges, prompting from a consortium of conservation groups, including CWA, Ducks Unlimited, and ĂŰčÖAPP. It is long past time to loosen the control the BOR holds over the basin’s water, so that stakeholders can explore creative and cooperative solutions that are more responsive to the needs of the refuges and their wildlife.

One such solution, albeit at a modest scale, emerged last fall with the purchase by the CWA of a small water right (3,750 acre-feet per year) from a willing seller in the Upper Klamath Basin. The CWA—a longtime advocate for the Klamath refuges—has transferred this right to the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge. This is a drop in the bucket of the 100,000 acre-feet that the refuge needs, but it is to be hoped that this precedent will lead to more sales of water rights. That could happen as more farmers conclude that the future for irrigated agriculture in the basin looks bleak.

In another encouraging development, the recently passed federal infrastructure bill includes $162 million to be used by the FWS for Surely some of that funding can be used to save the wetland habitat in these critically endangered refuges. Meanwhile, a plan to remove four of the dams blocking fish passage on the Klamath River is . Once complete, removing these barriers will open more than 400 miles of the river and tributaries to spawning and rearing by salmon and steelhead, and improve water quality and temperature conditions. That could ease demands on basin water to benefit these endangered fish.

Back on what should be the shore of Tule Lake, I return to my car and drive a mile or two to the only remnant of open water at the refuge. Scattered on its surface are a few Ruddy Ducks and coots. I stand there heavy with disappointment—but then I hear an unmistakable yodeling overhead. Looking up, I see a V of Snow Geese approach, brilliant white against the blue sky, and drop onto the far side of the lake. It isn’t much, but it feels like a beginning. I can only hope that this year, when waterfowl numbers touched bottom, marks the low point from which recovery can slowly begin.

Pepper Trail recently retired after a 23-year career as an ornithologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He lives in Ashland, Oregon.